| Walking in the Footsteps of Eranos |  |

|

|

| Congresses - 2004 Barcelona |

| Written by Bob Hinshaw, Paul Kugler |

| Friday, 11 September 2009 18:01 |

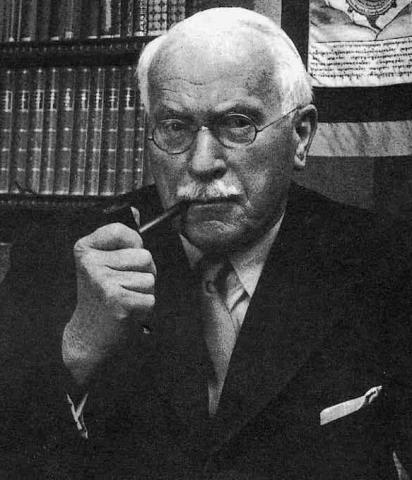

IntroductionRobert Hinshaw “Eranos, landscape on the lake, garden and house. Unpretentious, out of the way, and yet … a navel of the world, a small link in the golden chain.”1 These are the words of Erich Neumann: philosopher, psychiatrist, friend of C.G. Jung, participant at the Eranos Conferences for many years. With the chain, Neumann alludes to the alchemicalAurea Caténa – a link of wise beings, inspired by the force of Hermes Trismegistos, connecting heaven and earth. Another Eranos speaker, I Ching scholar Hellmut Wilhelm, once epitomized Eranos with the words of Confucius: “Friends gather at a well-tended place and together they prepare a pathway … for humanity.”2 As we can hear, tremendous admiration is being expressed for the phenomenon known as Eranos; also tremendous aspiration and ambition – fertile ground for the workings of the shadow, as time would tell. Why is a major portion of the program at our Congress being devoted to the spirit of Eranos? What does it have to do with Analytical Psychology today? The Eranos Conferences, beginning in 1933, proved to be a very fruitful place of exchange for professionals from a wide variety of fields.3 They also had a significant influence on the creativity and work of C.G. Jung. The inspiration that sustained the Eranos Conferences at such a high level over the decades struck the Program Committee as very fitting for this Congress, with its theme: Edges of Experience – Memory and Emergence. With a number of former Eranos participants among our members and honorary members, we asked a few of them to share their memories and reflections, and bring some of the Eranos spirit to our Congress. Eranos spawned much that is of importance to us today. Jung was a speaker from the very beginning, an enthusiastic participant for some twenty years. He developed and tested new ideas during his encounters with contemporaries from other fields, not only during the formal presentations but also at the famous round table on the Eranos patio, where many a debate transpired during mealtimes and between lectures. The Bollingen Foundation had its beginnings in the gardens of Eranos, and the plans for Jung’s Memories, Dreams, Reflections, were born there, in 1956. ARAS, the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism, an important part of our heritage and current research, grew out of the archetypal images collected by Eranos founder Olga Froebe-Kapteyn. Erich Neumann’s monumental work, The Great Mother, actually got its start when Jung and Olga Froebe suggested that Neumann write a dedication to a first publication of the original Eranos archive: Neumann’s writing on this subject so flourished that it came to replace the idea of publishing the Eranos Archive.4 We will be hearing more about the founder of Eranos and seeing photographs from the early days in the presentation to follow by Paul Kugler. For now, I will briefly introduce her and sketch the early history of Eranos. Olga Kapteyn was born in Bloomsbury, London, of Dutch parents in 1881. In the same year, Toni Wolff was born in Zurich, and Pablo Picasso in Malaga. Her father was a passionate amateur photographer and she reported that her later interest in archetypal images came from her fascination in watching photographs slowly emerge as her father developed films in the darkroom. Olga Kapteyn studied art history at the University of Zürich and then married Iwan Froebe, a Croatian orchestra conductor. Shortly after her husband’s death in a plane crash, their twin daughters were born in 1915. After World War I, Olga and her father went on holiday to Ticino, Italian Switzerland. They loved it so much that her father purchased a lakeside house near Ascona, soon to be hers. She built a small lecture hall on the grounds, and the setting for what was to become Eranos was in place. Her true calling as “The Mother of Eranos” came after a visit to German theologian Rudolf Otto, her meeting with Jung, and her decision to hold a conference on East-West themes. Professor Otto, author of The Idea of the Holy,5 suggested the Greek word eranos as a name evoking both the convivial spirit of an open interchange and the classical prototype of all such discussions, the Platonic symposium. The word eranos in ancient Greece referred to a banquet at which each guest showed worthiness of the invitation by presenting a gift: a song, a poem, an improvised speech. In August of 1933, a group of scholars assembled to initiate the first shared Eranos feast. Heinrich Zimmer and C.G. Jung were among the seven invited speakers. The common theme proposed by Frau Froebe was “Yoga and Meditation in East and West.” The lectures were delivered from the contrasting viewpoints of the speakers in German, English or French. The idea of an interdisciplinary conference with representatives from many fields of endeavor approaching a common theme is not at all unusual today, but at the time this conference was conceived, it was absolutely unique. The round table, fruitful setting for hearty exchanges became a special topos of Eranos. Jung wrote in a letter in 1951: “I recall with pleasure and gratitude countless evenings overflowing with stimulation and information, providing just what I so much needed … personal contact with other fields of knowledge.”6 The conferences took place in an intimate setting: the formal part in a small lecture hall in the lakeside garden and the informal at the famous table, where everyone present had an equal position. This stands in considerable contrast to today’s conference world of huge halls, hundreds of participants, and simultaneous translations and presentations. At Eranos there was intimate contact between the speakers and audience, and intimate contact with nature: alpine fauna and flora coexisting with tropical plants, southern sky on northern horizons. … At the first conference, Jung extemporaneously described ‘‘the Westerner,” in contrast to “the Easterner,” as: “disagreeable, a pirate, a conquistador, … disoriented and miserable in spite of his superabundance of knowledge and his intellectual arrogance.”7 He was well aware of the dangers of idealization, however, as he expressed in a letter to Olga Froebe not long after the conference: “Too much Eastern wisdom takes the place of immediate experience, and thus blocks the way to psychology.”8 The Eranos focus gradually shifted from the meeting of East and West to Europe’s meeting with multiple aspects of its own destiny. Eranos revealed its power to form, as well as to be formed by, the men and women who took part. It developed its own identity, beyond the boundaries originally set by its founder, to become a center where ideas were exchanged on science and the humanities, on religion and myth, on psychology and gnosis. Each conference was organized around a broad theme: Spiritual Guidance in the East and West(1935); The Configuration and the Cult of the Great Mother (1938); The Mysteries (1944); Spirit and Nature (1946); The World of Color (1972). The papers were published in highly regarded yearbooks, and selections edited by Joseph Campbell have been translated and published in English in the Bollingen Series.9 In a preface to the Bollingen Eranos Series edited by Joseph Campbell, Olga Froebe wrote of the primary goal of the lectures: “It has not been literary perfection nor necessarily a total treatment of the subject. Their value is evocative. In many cases, they carry us to the bounds of scholarly investigation and discovery, and point beyond.”10 One of the smallest but most impressive conferences took place during the war, in 1940. Actually, only a symbolic get-together was planned, because the conditions of that time prohibited the attendance of any speakers from outside the country. The only scheduled lecture was by theologist Andreas Speiser on “The Platonic Doctrine of the Unknown God and the Christian Trinity.”11 The Jungs were there and with them about a dozen friends and students. Jung was most impressed by the lecture and that afternoon, he asked for a Bible, drew back into the garden, and made it known that he did not wish to be disturbed. The next day, he improvised a lecture of response, “On the Psychology of the Trinity.”12 Aniela Jaffé has described how hearing and watching his slowly-forming thoughts on this great theme, sentence by sentence, was a moving experience of the spirit, in statu nascendi.13 Jung’s full-length published paper on this theme was not to appear for another eight years. After Jung’s time, which ended in the early 1950s, Eranos continued for several decades to be a center where a handful of Jungian colleagues came together with leading figures from other fields to present their newest research and to be stimulated. Some of the many well-known speakers to participate in the Eranos Conferences were: writer/ humanist Martin Buber (1878-1965), mythologist Joseph Campbell (1904-1987), Islamist Henry Corbin, religious historian and author Mircea Eliade, Jungian analysts Marie-Louise von Franz (1915-1998) and Aniela Jaffé (1903-1991), mythologist Karl Kérenyi, Swiss biologist Adolf Portmann, writer/explorer Laurens van der Post (1906-1986), English poet Kathleen Raine, Kabbalist Gershom Scholem, Japanese Zen master Daisetz Suzuki (1870-1966), German/American theologian Paul Tillich (1886-1965), Dominican priest Father Victor White (1902-1960), Indologist Heinrich Zimmer (1890-1943). We’ve already heard the names Neumann, Wilhelm, Otto and Jung. The list could go on much longer, but I’ll just mention our own speakers at this Congress, all of whom participated in numerous Eranos conferences: Gilles Quispel, James Hillman, Hayao Kawai, David Miller. Geographically, Eranos is located at the southern-most tip of Switzerland, bordering on Italy; north-south travelers between the Mediterranean and central Europe pass through this valley on their way to or from the grand old Swiss passes through the Alps. It also marks a cultural north-south border. The Monte Verità, famous as the birthplace of various avant garde movements in the first half of the twentieth century, is within easy walking distance. Eranos is beautifully situated at the edge of many far-reaching influences, and naturally cross-fertilization occurs. This area around the little town of Ascona, and Eranos within it, has long been a kind of small renaissance center of the arts and sciences. It was characteristic of Eranos that speakers did not address themselves to an audience of specialists; yet, neither did they engage in “popularization.” Eliade commented: “The originality of Eranos lies primarily in the fact that the speakers … are able to shed both their timidities and their superiority complexes.”14 Eranos was a kind of living pladoyer for diversity and the riches resulting from many perspectives. In its spirit, we recall not only many presences, but a “being present:” Corbin, describing the particular atmosphere of Eranos, once wrote: “What we should wish to call the meaning of Eranos, which is also the entire secret of Eranos, is this: it is our present being, the time we act personally, our way of being.”15 It is a “… meeting of … autonomous individualities, each in complete freedom revealing and expressing an original and personal way of thinking and being, outside of all dogmatism and all academics.”16 My own introduction to Eranos came in 1971. I was a young beginning student at the Zürich Institute and also participated in some “off-campus” discussions known as the Spring House gatherings. One of the subjects addressed was the puer aeternus, and when the group wanted to continue with this topic in a more intense manner, James Hillman suggested our doing so over a weekend on the grounds of Eranos. At the time, many of us had never heard of the place. It was to be an unforgettable event and in my case, the beginning of a relationship that has continued ever since. We found ourselves truly inspired by the ideas brewing and flying around at the table and in the gardens: the genius loci was having its powerful effect. As we were to learn later, we were far from alone in having such an Eranos experience. Today, hard times have fallen upon Eranos: in terms of its raison d’etre and also financially, it finds itself in a life-and-death struggle, whose outcome is yet to be seen. The last of the regular August Conferences was held in 1988, replaced in the following years by a series of I Chingconferences led by the Director, Rudolf Ritsema. Within a year, a group of former participants created a new organization known as Amici di Eranos, Friends of Eranos, and began to hold their own annual meetings in the nearby town of Ascona. We see that splitting is practiced not only by Jungians! Eranos itself went through many changes in subsequent years, and found itself in ever more serious financial difficulties. At present, there are hopes, with the participation and support of the local government, to again make it into an international conference center, based on the model created and practiced by Olga Froebe. References

Eranos and Jungian Psychology: A History in ImagesPaul Kugler The Eranos Conferences represent one of the most remarkable achievements in the history of analytical psychology. Intellectual traditions from the Far East, the Middle East and the West came together at Eranos for over half a century: Max Knoll from Princeton lectured alongside of Corbin from Tehran and Paris, Jung from Switzerland and Suzuki from Japan. At its core, Eranos was inter-disciplinary and multi-cultural, with speakers from various cultures presenting on religion, philosophy, literature, science, psychology and medicine. Different cultures, different disciplines and different languages came together in Ascona for eight days each August for lectures and over dinner. Olga Froebe expressed her vision of Eranos as a process of gradually building up a multi-disciplinary picture of the inner transformations of the psyche.*

This photograph is of the Eranos Round Table. During the conferences, speakers and guests would share meals together at the round table and discuss the lectures. The Eranos Conferences took place on the shores of the Lago Maggiore, a short distance from Ascona, each August beginning in 1933. This photograph is of Ascona in the 1930’s, located in the southern Italian speaking part of Switzerland.

Olga Froebe, the originator of the conferences, is seen in this 1933 photograph standing on a garden walk just above Casa Eranos where the lecture hall is located.

This picture of Olga Froebe was taken in 1920. She was born in 1881 in London of Dutch parents and grew up in Bloomsbury. Her father, Albert Kapteyn, was an inventor, a photographer and director of the London office of Westinghouse; her mother, Gertrude, was a writer on social issues and friend of George Bernard Shaw.

Olga later studied applied art in Zürich and married Irwin Froebe, an Austrian musician. While testing one of the first aerial cameras in 1915, Irwin died following a plane crash.1 Around 1920, Olga Froebe and her father traveled to Ascona for a vacation. They liked the town and her father bought Casa Gabriella for his daughter. The building in the middle is Casa Gabriella, originally purchased by Froebe’s father, along with most of the land you see in the photograph. In 1928, Froebe built a guest house, seen here on the right, called Casa Shanti. That same year she also built a lecture hall on the left, overlooking the lake.

This photograph was taken inside of the Eranos lecture hall. Froebe felt an urge to create some kind of public format to provide a meeting place between East and West, especially around issues of spirituality, aesthetics and inner transformation.

This photograph of Rudolf Otto was taken in 1933. While Froebe had occasionally used the word “Eranos” on her letter head in the early 1930’s, it was not until she met with Rudolf Otto in November of 1932, that she settled on the name “Eranos” for the conferences. Otto was a distinguished scholar of comparative religions and mysticism, particularly known for his book, The Idea of the Holy. Froebe described to him the lecture hall and her plan for an annual multi-disciplinary conference which would bring together leading scholars from the East and the West. Otto responded warmly to her plan and to the name “Eranos,” which in ancient Greek means “a shared feast” or “picnic” to which each of the participants brings their own contribution. The original Greek meaning described well Froebe’s underlying idea for the conference.2

The first lecturer Froebe sought out after speaking with Otto was Heinrich Zimmer, a professor of Indology at Heidelberg. Zimmer accepted enthusiastically and lectured at Eranos from 1933 to 1939. This photograph of Zimmer was taken at the 1935 conference.

Olga initially met Jung in 1930 at Hermann Keyserling’s School of Wisdom in Darmstadt. Following her conversation with Otto, she invited Jung to speak at the first Eranos Conference in August 1933. Jung accepted her invitation and lectured the first year on “The Psychological Process of Individuation.” Froebe and Jung are standing outside of Casa Eranos in this 1933 photograph.

Jung spoke at Eranos from 1933 to 1951, ten years before his death. During the 1930s and 40s, Eranos was a place where he first discussed many of his most important ideas. The conferences presented Jung’s work in a new light, as a dialogue with world renowned scholars from many different cultures and disciplines. Emma and Carl Jung are seen in this 1933 photograph sitting on the wall just outside of the lecture hall overlooking the lake.

In 1924 Froebe attended a seminar by Martin Buber at nearby Monté Verità and initiated a correspondence with him.3 Ten years later she invited Buber to lecture at the second conference. This photograph of Buber was taken at Eranos in 1934. Long before Jolanda Jacobi moved to Zürich in the late 1930s, she attended the Eranos Conferences.4 In this 1935 photograph, Jacobi is seen standing just inside the lecture hall looking out of the window towards Gustav Heyer. Born in Budapest, Jacobi underwent both a Freudian and an Adlerian analysis in Vienna, before moving to Zürich to train with Jung. In 1948, she took a leading role in founding the Jung Institute in Zürich.

This photograph of Jung and Zimmer was taken at the 1936 Eranos. The title of Jung’s presentation that year was “The Idea of Redemption in Alchemy.” Paul Tillich also lectured at the 1936 conference and again in 1954.

The steep terrain surrounding the three Eranos buildings is evident in this 1936 photograph. Jung can be seen here walking with friends up to the street level from the lecture hall located some distance below.

This portrait of John Layard was taken at the 1936 Eranos. Layard was a distinguished Oxford anthropologist, as well as a Jungian analyst. He wrote extensively on the inter-relation between anthropology and analytical psychology and his most important book is a study of The Stonemen of Malakula. Layard gave five Eranos lectures between 1937 and 1959. During the 1938 conference, Froebe introduced a new feature, an exhibition of enlarged photographs from the archive she had been compiling on archetypal symbolism.

This photograph of Jung and Aniela Jaffé sitting on the wall outside of the Eranos lecture hall was taken in 1938. The title of Jung’s lecture that year was “Psychological Aspects of the Mother Archetype.”

The woman on the left in this 1938 photograph is Mary Mellon, the motivating force behind the establishment of the Bollingen Foundation. 5 Jung gave his Terry lectures at Yale University in October of 1937 and following the lectures, he conducted a dream seminar for the Analytical Psychology Club of New York. Mary and Paul Mellon attended the seminar and were so moved by the experience that the following Spring the Mellon family traveled to Zürich and Mary began attending Jung’s English seminar. After the seminar recessed for the summer, the Mellons traveled to Ascona to meet Froebe and visit Eranos. Later Mary Mellon wrote to Froebe about her visit to Eranos in the following way: “The first thought that went through my mind when I stepped onto the terrace at Casa Gabriella was ‘This is where I belong.’”6

The man on the right in the photograph is Louis Massignon. Louis Massignon, a scholar of Islamic mysticism, was one of the new speakers at the 1939 Eranos. He opened the conference with his talk on “Resurrection in the Mohammedan World.” Massignon lectured from 1939 to 1955. This photograph of Jung and W. F. Otto, the distinguished classicist, was taken at the 1939 conference. Otto authored such classic texts as The Homeric Gods and Dionysus. He lectured at the 1939 conference and again in 1955.

This photograph of Paul Mellon and Zimmer was taken at the 1939 conference. That year Mary Mellon was thirty-five years old and beginning to formulate her ideas about what would later become the Bollingen Foundation. Particularly moved by the lectures of Zimmer and Massignon, she would later publish their works in the Bollingen series. In 1940 Zimmer fled Germany with his family and eventually took up residence in New York City. He secured a teaching position at Columbia University and, in 1943, gave a series of private seminars at the apartment of the anthropologist, Maud Oakes. Joseph Campbell, a graduate student at Columbia University, began to attend the classes at Oakes apartment. Part way through the seminar, Zimmer developed a severe cold, but instead of taking time off to rest, he continued to teach. His cold developed into pneumonia and Zimmer died seven days later at the age of fifty-two.7 Zimmer was a major influence on Joseph Campbell’s work. After his death, Campbell spent many years preserving and publishing Zimmer’s lectures and supervising the translation of his books into English.

In 1940, due to the war and travel restriction, Froebe arranged for a symbolic Eranos conference. Only one speaker, Andreas Speiser, a Swiss professor of mathematics at the University of Zürich, was scheduled to give a lecture on “Plato’s Unknown God.” Unexpectedly, forty people attended, including Jung, who gave an extemporaneous lecture on “The Psychology of the Trinity.” Jung and Speiser appear together outside of the lecture hall in this 1940 photograph.

The 1941 conference, again affected by the war, consisted of only four lecturers and was held in early August. Karl Keré nyi, a professor of classical philology in Hungary, lec tured for the first time that year. He had been a student of W. F. Otto and earlier he had been introduced to Jung by Jolanda Jacobi, a fellow Hungarian. In 1939 Kerényi collaborated with Jung on a book entitled: “Introduction to a Science of Mythology.” This photo graph of Kerényi was taken in 1941. Among the Eranos lec turers, Kerényi was one of the most dramatic, with a mane of white hair, deep- set piercing eyes, and a charismatic presence. Kerényi lectured at Eranos from 1940 to 1950 and was very popular with the audience. In 1950, Froebe, feeling he had become too charasmatic a presence, no longer invited him. After Froebe’s death in 1962, Kerényi was asked to lecture again at the 1963 conference.8

This photograph is of Jung and Medard Boss at the 1942 Eranos. Boss was one of the founders of existential psychoanalysis. He studied with Freud in Vienna and under Bleuler at the Burghölzli Klinik in Zürich before beginning a ten year affiliation with Jung in 1938. During this time, Jung invited Boss to join a clinical seminar held at his home every fortnight to discuss cases with a group of therapists of various orientations.9 In 1947 Jung and Boss had a falling out over the question of giving precedence to theory over clinical phenomena, each accusing the other of the same failing.10 In May of 1943, Mary Mellon officially approved the establishment of the Bollingen Series. Later she would write: “Bollingen is my Eranos.”11 This photograph of Mary Mellon was taken during a visit to Eranos.

The 1943 Eranos Conference was the first in ten years at which Jung did not appear on the program. 12 This portrait of Hugo Rahner was taken at the 1943 conference. His Jesuit community from Innsbruck sought refuge in Switzerland during the war and from 1942 to 1948 Rahner lectured at Eranos on Christian mysticism.

While Jung attended the 1944 conference, he again did not lecture. Earlier in February of that year, Jung had broken his leg and while recovering in hospital, he suffered a near fatal heart attack.

This photograph of Jung and Erwin Schrödinger was taken in a garden near the Round Table at the 1946 confer ence. The conference theme that year was “Spirit and Nature.” Jung lectured on “The Spirit of Psychology”and Schrödinger spoke on “The Spirit of Natural Science.” A theoretical physicist, Schrödinger won the Nobel Prize in 1933 for his discovery of the Schrödinger wave equation.

This portrait of Adolf Portman was taken at the1949 conference. He was a distinguished professor of biology at the University of Basel and lectured from 1946 to 1977, a total of thirty-one years. Following Froebe’s death in 1962, he became a guiding force at Eranos. Portman’s life long project was to give biology an orientation that is both ethical and aesthetic. In 1946, he lectured at Eranos for the first time. On October 11th, six weeks after the conclusion of the 1946 conference, Mary Mellon suddenly died at the age of forty-two. At the time, she had been living at her home in Virginia overseeing the Bollingen Foundation. Mary Mellon had gone fox hunting with her husband in the morning and suffered an asthma attack. She was unable to receive immediate treatment because during the ride the applicator containing her medication had broken. The attack grew more severe and later that afternoon she died of a heart attack. Only a year before her death, Mary Mellon had begun talking about the possibility of buying Eranos to make it financially sound and officially bringing together Eranos and Bollingen.

Several years after her death, Froebe approached Paul Mellon about Mary’s offer to buy Eranos. Paul Mellon had by now remarried and no longer was inclined to pursue Mary’s plan to purchase the property.13

This photograph of Jung and Leo Beck was taken at the 1947 Eranos. Jung and Baeck had met many years before at Key serling’s “School of Wisdom” in Darmstadt. During World War II, Baeck, the Rabbi of Berlin, had at age sixty-nine followed his congregation to the concentration camp. He had been one of only a few members to survive. Baeck lectured at the 1947 Eranos.14

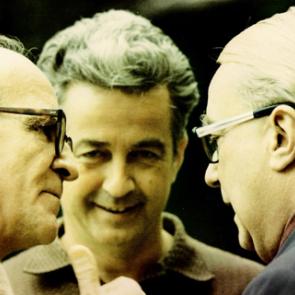

Gilles Quispel is the man on the left next to Adolf Portman in this 1947 photograph. A Dutch Gnostic s c h o l a r, Quispel, then in his early 30s, became one of the youngest persons ever invited to lecture at Eranos. He went on to give thirteen lectures between 1947 and 1971. The year 1947 was a milestone in the history of Gnostic studies. In the winter of 1947, shortly after the discovery of thirteen Gnostic codicies in upper Egypt, one of the manuscripts was offered for sale to the Bollingen Foundation. The offer was declined by Bollingen. At the time, Quispel, a young Dutch Gymnasium teacher with an expertise in church history, decided to intervene. Quispel eventually located the codex and secured funding with the help of C. A. Meier, and on the 10th of May, 1952, he acquired the Codex for the Zürich Jung Institute. The manuscript became known as “The Codex Jung” and has since played a significant role in our understanding of Gnosticism.15

In Casa Gabriella, on August 25, 1947, just after the completion of that year’s Eranos Conference, Jung signed the contract with Bollingen and Kegan Paul for the English translation of his collected works. Herbert Read, a senior editor at Kegan Paul, proposed R. F. C. Hull as the official translator for Jung’s Collected Works. This photograph of Hull was taken in Casa Gabriella in the 1950s. Hull was a former medical student turned poet, journalist and translator who had worked as a cryptographer during the war. Within four months of the signing of the contract, Hull was admitted to a hospital in England with polio affecting all four limbs. Nevertheless, by January of that year Hull was busy dictating his translation of Psychology and Alchemy to his wife while lying on his back. Hull went on to translate nearly all of Jung’s Collected Works, with the exception of Volume Two, Experimental Studies.16

Eric Neumann lectured at Eranos between 19481960. This photograph of Neumann was taken at the 1948 conference. Born in Germany in 1905, Neumann was a student of literature and Jewish mysticism prior to entering medical school. He had a Ph.D. in philosophy, but had to leave Germany for Tel Aviv in 1934 before completing his Medical Degree. In 1947 he traveled to Europe to visit his old childhood friend, Gerhard Adler, vacationing in Ascona. Adler introduced Neumann to Froebe and Eranos.17

Impressed by Neumann, Froebe invited him to lecture at Eranos the following year. The title of his lecture was “Mystical Man.” Froebe introduced Neumann to her picture archive, hoping he might write on the various archetypal themes she had collected over the previous ten years. Neumann started with her collection of the archetypal feminine and the result was his book, The Great Mother, illustrated with over 250 pictures, mostly from the Eranos archive.

This photograph of Neumann and John Layard was taken in 1958. Neumann gave thirteen Eranos lectures between 1948 and 1960. Shortly after giving his final lecture in 1960, Neumann died from cancer at age fifty-five.

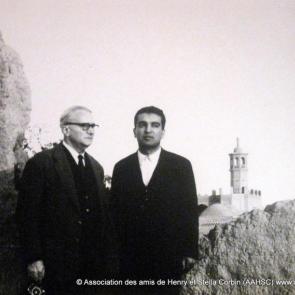

Henry Corbin, a world renowned scholar of Sufism, appears with Jung in this 1951 photograph. Several years earlier, Corbin had been introduced to Eranos by Louis Massignon, also a scholar of Islamic mysticism. Corbin lectured at Eranos for twenty-seven years, between 1949 and 1976. During most of his academic life, he divided his teaching time between Paris and Tehran.

This portrait of Gershom Scholem was taken in 1949, the first year he appeared on the conference schedule. One of the pre-eminent scholars of Jewish mysticism, Scholem was a gifted lecturer with a wonderful sense of humor. He spoke at Eranos for thirty years, from 1949-1979.

Corbin knew Eliade in Paris and introduced him to Eranos in 1949. The following year, Eliade was invited to lecture on “Psychology and the History of Religions.” This portrait taken at the 1949 conference. Eliade lectured at Eranos from 1950 to 1967.

In addition to round table discussions, Jung started a tradition known as the “terrace-wallsessions.” Immediately following a lecture or during intermission, Jung and friends would gather by the stone wall of the terrace and discuss the psychological significance of the presentation.18 This photograph of Jung in conversation with a small group of participants by the terrace wall was taken at the 1951 conference.

Max Knoll, a professor of physics from Princeton University, lectured at Eranos between 1951 and 1965 on the history of science. This photograph of Knoll was taken at the 1951 conference. In 1934 Knoll and Ernst Ruska, his student, invented the electron microscope. Knoll died in 1969, seventeen years before his co-inventor, Ruska, would be awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for their invention of the electron microscope.

This photograph of Emma Jung sitting on the wall just outside of the lecture hall, was taken in 1951. The theme of the conference that year was “Man and Time.”

Gerhard Adler, Neumann and Quispel are seen in this photograph sitting just outside the lecture hall at the 1951 conference. When Bolligen and Kegan Paul prepared to translate and publish Jung’s Collected Works, they appointed Herbert Read and Michael Fordham as editors. Jung requested that Gerhard Adler also be made a co-editor because of his understanding of the intricacies of the German language.19

Jung delivered his final Eranos lecture in 1951, entitled: “On Synchronicity.” His lecture was later expanded and published in a book, co-authored with the Nobel Laureate in physics, Wolfgang Pauli.

Ira Progoff, Suzuki and Miroko Amura are seen in this 1953 photograph sitting at the round table. A professor at Drew University Graduate School, Progoff studied with Jung in the early 1950s. Progoff lectured at Eranos between 1963 and 1966.

This photograph of Joseph Campbell, Jean Erdman his wife, Hull and his son Jeremy was taken in 1953 in Ascona. Campbell began a project in 1949 for the Bollingen Foundation to publish a series of English translations of selected Eranos lectures. Six volumes of “Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks” were eventually published (1954-1968) under such titles as Man and Time, Spirit and Nature, and Man and Transformation. In 1953 Campbell attended the Eranos Conference for the first time, and returned in 1957 and again in 1959 to lecture himself.

This photograph of Kurt Wolff was taken at Eranos in the 1950s. The founder of Pantheon Books, Wolff was the Bollingen Foundation publisher for almost twenty- five years. While attending the 1956 Eranos conference, Wolff persuaded Jung to write his autobiography in collaboration with Aniela Jaffé. Immediately following the Conferences during the 1950s, Wolff representing Pantheon Books, Herbert Read representing Kegan Paul, and Vaun Gillmor representing the Bollingen Foundation, would meet with Jung to discuss the progress of the English translation of the Collected Works.

In 1956 Froebe donated the Eranos Picture Archive to the Warburg Institute in London and gave duplicates to the Jung Institute in Zürich and the Jung Foundation in New York. The Eranos Picture Archive in New York later grew into what we know today as the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism (ARAS).

This photograph of Froebe with a Dutch couple, Rudolph and Catherine Ritsema, was taken in 1958. After Froebe’s death, the Ritsemas took over management of the Eranos Foundation.

Eranos has many beautiful terraced gardens with multiple paths at different levels connecting the three buildings. This carved stone is located in the garden of Casa Gabriella and has a Greek dedication suggested by Jung which translates, “To the unknown genius of this place.” When Froebe died on April 25, 1962, her ashes were interred beside this monument.

In 1963, following Froebe’s death, Kerényi was again asked to lecture at Eranos. Vaun Gillmor, seated next to Kerényi, was one of the Bollingen representatives meeting yearly with Jung after Eranos to oversee the publication of his Collected Works.

This photograph of Scholem and Quispel was taken at the 1965 conference. Each year lectures were divided between French, English, German and occasionally Italian. Quispel was the only speaker to lecture in three different languages: twice in French, seven times in German and four in English.

Izutsu lectured at Eranos on Zen Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism between 1967-1982. He always lectured wearing traditional Japanese attire. This photograph of Izutu was taken at the 1967 conference.

While serving as the Director of Studies at the Jung Institute in Zürich, James Hillman attended the 1964 conference. He had the intention of inviting Eranos speakers to lecture at the Institute. Ironically, he was invited, instead, to speak at Eranos. Hillman gave his first Eranos lecture at the 1966 conference, entitled “On Psychological Creativity.” This photograph of Rudolph Ritsema and Hillman was taken at the 1969 Conference.

Aniela Jaffé spoke at Eranos four times between 1971 and 1975. Her final lecture entitled, “C.G. Jung and the Eranos Conferences,” was in honor of Jung’s 100th birthday. This portrait of Jaffé was taken at the 1972 conference.

In 1975, David Miller lectured at Eranos for the first time. Miller studied with Owen Barfield and Stanley Hopper at Drew University, before going on to hold the Watson-Ledden Chair in Religion at Syracuse University. This photograph of Miller and Ritsema was taken in 1975.

Henry Corbin presented at Eranos for over twenty-five years between 1949 and 1976.21 This photograph of Corbin sitting on the bench behind the round table is from 1976, the year he delivered his final Eranos lecture.

A distinguished French philosopher of the imagination, Gilbert Durand spoke at Eranos between 1964 and 1988. For his activity during World War II in the French resistance movement, Durand was awarded the Legion of Honor Medal. This photograph of Durand lecturing is from the 1980 conference.

Eranos presented a modest image to the public. From the road, this sign is the only visible indication of the Eranos foundation. A little bulletin board just below the Eranos sign contained a copy of the current year’s conference schedule.

In this photograph David Miller is delivering his 1980 lecture, entitled “Between God and the Gods – Trinity.” The conference theme that year was “Extremes and Borders.” Miller delivered nine Eranos lectures between 1975 and 1988.

Erik Hornung, a world renown Egyptologist from the University of Basle, lectured between 1977-1987. Among his many books is Knowledge of the Afterlife, co-authored with Theodor Apt. Hornung is seen lecturing at the 1980 conference in this photograph.

The seating at lunch and dinner during the conferences was carefully arranged in advance according to which languages each person spoke. Often French and Italian speakers were grouped at one table, with German and English speakers at the other.

In this 1982 photograph, Wolfgang Giegerich is be seen delivering his first Eranos lecture. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley, taught at Rutgers University and later trained at the Jung Institute in Stuttgart. Between 1982 and 1988, Giegerich delivered seven Eranos lectures.

This picture was taken at the 1988 conference. Hillman, Giegerich and myself are looking over photographs taken during previous conferences. The 1988 Eranos Conference was the final one based on Froebe’s original design. The decision to stop the conferences came about for a variety of reasons, including financial concerns and a shift in focus as to the mission of Eranos. While seminars and conferences continue to be held at Eranos and a local hotel, 1988 was the last conference located at Casa Eranos in the format originally conceived by Olga Froebe.

References

|

http://iaap.org/congresses/barcelona-2004/walking-in-the-footsteps-of-eranos.html

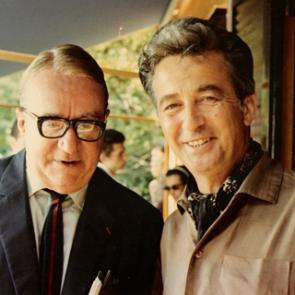

T h i s p h o t o - graph of conference participants milling around outside thelecture hall was taken at the 1958 Eranos . Herbert Read, the tall man with white hair on the left, was an English poet, art historian, and publishing editor. As a director at Kegan Paul, Read oversaw the publication of Jung’sCollected Works. For twelve years between 1952 and 1964, Read lectured at Eranos.

T h i s p h o t o - graph of conference participants milling around outside thelecture hall was taken at the 1958 Eranos . Herbert Read, the tall man with white hair on the left, was an English poet, art historian, and publishing editor. As a director at Kegan Paul, Read oversaw the publication of Jung’sCollected Works. For twelve years between 1952 and 1964, Read lectured at Eranos. This photograph of Ernst Benz and D. T. Suzuki was taken at the 1953 conference. Benz, on the left, is a world renowned scholar of comparative religions, who lectured at Eranos between 1953 and 1978. The Zen Buddhist, D. T. Suzuki, was in his 80s when Max Knoll recommended he be invited to lecture at Eranos. Jung had earlier written an extensive foreword to Suzuki’s book, “Introduction to Zen Buddhism.”20

This photograph of Ernst Benz and D. T. Suzuki was taken at the 1953 conference. Benz, on the left, is a world renowned scholar of comparative religions, who lectured at Eranos between 1953 and 1978. The Zen Buddhist, D. T. Suzuki, was in his 80s when Max Knoll recommended he be invited to lecture at Eranos. Jung had earlier written an extensive foreword to Suzuki’s book, “Introduction to Zen Buddhism.”20

On the left in this 1980 photograph is Alfred Zeigler, a physician and Jungian analyst from Zürich with an expertise in psychosomatic medicine. Zeigler lectured for the first time in 1980 and again in 1984. On the right is Jean Brun, a distinguished French philosopher of religion who lectured at Eranos from 1975 to 1988.

On the left in this 1980 photograph is Alfred Zeigler, a physician and Jungian analyst from Zürich with an expertise in psychosomatic medicine. Zeigler lectured for the first time in 1980 and again in 1984. On the right is Jean Brun, a distinguished French philosopher of religion who lectured at Eranos from 1975 to 1988.

Patricia Berry can be seen seated on the front right in this picture of the 1982 round table. David Miller is in the back on the left, and his wife, Patricia Cox, is seated opposite him with her back to the camera. Erik Hornung can also be seen at the far side of the table.

Patricia Berry can be seen seated on the front right in this picture of the 1982 round table. David Miller is in the back on the left, and his wife, Patricia Cox, is seated opposite him with her back to the camera. Erik Hornung can also be seen at the far side of the table.

James Hillman and Adolf Guggenbühl are seen in this photograph at the 1982 conference. Hillman’s lecture that year was entitled: “The Animal Kingdom in the Human Dream.”

James Hillman and Adolf Guggenbühl are seen in this photograph at the 1982 conference. Hillman’s lecture that year was entitled: “The Animal Kingdom in the Human Dream.” This portrait of Kawai, the first Jungian analyst in Japan, was taken at the 1983 conference. He lectured at Eranos between 1983 and 1988 on Japanese mythology, spirituality and fairytales. A professor of clinical psychology at Kyoto University and president of the Association of Japanese Clinical Psychology, Kawai currently holds the distinguished position of Minister of Culture in Japan.

This portrait of Kawai, the first Jungian analyst in Japan, was taken at the 1983 conference. He lectured at Eranos between 1983 and 1988 on Japanese mythology, spirituality and fairytales. A professor of clinical psychology at Kyoto University and president of the Association of Japanese Clinical Psychology, Kawai currently holds the distinguished position of Minister of Culture in Japan. Toshio Kawai, Wolfgang Giegerich and David Miller are seen in this 1983 photograph taken on the veranda just outside of the lecture hall. Toshio Kawai, at the time, was completing his Ph.D. in Germany, while training at the Jung Institute in Zürich. Currently he is a professor at Kyoto University.

Toshio Kawai, Wolfgang Giegerich and David Miller are seen in this 1983 photograph taken on the veranda just outside of the lecture hall. Toshio Kawai, at the time, was completing his Ph.D. in Germany, while training at the Jung Institute in Zürich. Currently he is a professor at Kyoto University. In this photograph Hillman is seen presenting his 1985 lecture, entitled: “On Paranoia.” The conference theme that year was “The Hidden Course of Events.” Between 1966 and 1987, Hillman delivered a total of fifteen Eranos lectures, more than either Jung or Neumann.

In this photograph Hillman is seen presenting his 1985 lecture, entitled: “On Paranoia.” The conference theme that year was “The Hidden Course of Events.” Between 1966 and 1987, Hillman delivered a total of fifteen Eranos lectures, more than either Jung or Neumann. In 1978, and again in 1985, Marie-Louise von Franz lectured at Eranos. This photograph of von Franz was taken at the 1985 conference. The title of her lecture that year was “Nike and the River Styx.”

In 1978, and again in 1985, Marie-Louise von Franz lectured at Eranos. This photograph of von Franz was taken at the 1985 conference. The title of her lecture that year was “Nike and the River Styx.”

This is the view participants enjoyed looking out from Casa Eranos, across the Lago Maggori to the Italian Alps. While the Eranos conferences officially came to an end in 1988, the significance of its intellectual, cultural and psychological legacy continues to live on and grow in historical significance with each passing year.

This is the view participants enjoyed looking out from Casa Eranos, across the Lago Maggori to the Italian Alps. While the Eranos conferences officially came to an end in 1988, the significance of its intellectual, cultural and psychological legacy continues to live on and grow in historical significance with each passing year.